Travancore

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (September 2024) |

Kingdom of Travancore Thiruvithaamkoor Rajyam | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1729–1949 | |||||||||

| Motto: ധർമോസ്മത്ത് കുലദൈവതം Dharmōsmat Kuladaivatam (English: "Charity is our household divinity") | |||||||||

| Anthem: വഞ്ചീശ മംഗളം Vancheesha Mangalam (1937–1949) (English:"Hail the Lord of Vanchi") | |||||||||

Location of the Kingdom of Travancore (in red) in India (in green) | |||||||||

| Common languages | Malayalam (official) Tamil (Minority) | ||||||||

| Religion | Majority: Hinduism (official) Minority: Chiefly Christianity and Islam Small communities of Jews, Jains, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Zoroastrians | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

• 1729–1758 (first) | Marthanda Varma | ||||||||

• 1829–1846 (peak) | Swathi Thirunal | ||||||||

• 1931–1949 (last) | Chithira Thirunal | ||||||||

| Diwan | |||||||||

• 1729–1736 | Arumukan Pillai | ||||||||

• 1838–1839 (peak) | R. Venkata Rao | ||||||||

• 1947–1949 (last) | P. G. N. Unnithan | ||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Imperialism | ||||||||

• Established | 1729 | ||||||||

• Subsidiary alliance with the East India Company | 1795 | ||||||||

• Vassal of India | 1947 | ||||||||

• Merger with Kingdom of Cochin | 1 July 1949 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1949 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1941[1] | 19,844 km2 (7,662 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1941[1] | 6,070,018 | ||||||||

| Currency | Travancore Rupee | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

The Kingdom of Travancore (/ˈtrævəŋkɔːr/), also known as the Kingdom of Thiruvithamkoor (Malayalam: [t̪iɾuʋid̪aːŋɡuːr]) or later as Travancore State, was a kingdom that lasted from c. 1729 until 1949. It was ruled by the Travancore Royal Family from Padmanabhapuram, and later Thiruvananthapuram. At its zenith, the kingdom covered most of the south of modern-day Kerala (Idukki, Kottayam, Alappuzha, Pathanamthitta, Kollam, and Thiruvananthapuram districts, major portions of Ernakulam district, Puthenchira village of Thrissur district) and the southernmost part of modern-day Tamil Nadu (Kanyakumari district and some parts of Tenkasi district) with the Thachudaya Kaimal's enclave of Irinjalakuda Koodalmanikyam temple in the neighbouring Kingdom of Cochin.[2] However Tangasseri area of Kollam city and Anchuthengu near Attingal in Thiruvananthapuram were parts of British India.

Malabar District of Madras Presidency was to the north,[3] the Madurai and Tirunelveli districts of Pandya Nadu region in Madras Presidency to the east, the Indian Ocean to the south, and the Arabian Sea to the west.[4]

Travancore was divided into five divisions: Padmanabhapuram, Thiruvananthapuram, Quilon, Kottayam, and Devikulam. Padmanabhapuram and Devikulam were predominantly Tamil speaking regions with small Malayalam speaking minorities.[5] The divisions of Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, and Kottayam were predominantly Malayalam speaking regions with small Tamil speaking minorities.[5]

King Marthanda Varma inherited the small feudal state of Venad in 1723, and built it into Travancore. Marthanda Varma led the Travancorean forces during the Travancore-Dutch War of 1739–46, which culminated in the Battle of Colachel. The defeat of the Dutch by Travancore is considered the earliest example of an organised power from Asia overcoming European military technology and tactics.[6] Marthanda Varma went on to conquer most of the smaller principalities of the native rulers.

The Travancore royal family signed a treaty with the British in 1788, thereby adopting British dominance. Later, in 1805, they revised the treaty, leading to a diminution of royal authority and the loss of political independence for Travancore.[7][8] They had to give up their ruling rights over the common people in 1949 when Travancore were forced to merge with independent India.

Etymology

[edit]The kingdom takes its name from Thiruvithamcode in the present-day Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu.

The region had many small independent kingdoms. Later, at the peak of the Chera-Chola-Pandya, this region became part of the Chera Kingdom (except for the Ay kingdom, which always remained independent). When the region was part of the Chera empire, it was still known as Thiruvazhumkode. It was contracted to Thiruvankode, and anglicised by the English to Travancore.[9][10][11]

In the course of time, the Ay clan, part of the Chera empire, which ruled the Thiruvazhumkode area, became an independent kingdom, and the land was called Aayi Desam or Aayi Rajyam, meaning 'Aayi territory'. The Aayis controlled the land from the present-day Kollam district in the north, through Thiruvananthapuram district to Kanyakumari district in the south. There were two capitals, the major one at Kollam (Venad Swaroopam or Desinganadu) and a subsidiary one at Thrippapur (Thrippapur Swaroopam or Nanjinad). The kingdom was thus also called Venad. Kings of Venad had, built residential palaces in Thiruvithamcode and Kalkulam. Thiruvithamcode became the capital of the Thrippapur Swaroopam, and the country was referred to as Thiruvithamcode by Europeans even after the capital had been moved in 1601 to Padmanabhapuram, near Kalkulam.[12]

The Chera empire had dissolved by around 1100 and thereafter the territory comprised numerous small kingdoms until the time of Marthanda Varma who, as king of Venad from 1729, employed brutal methods to unify them.[13] During his reign, Thiruvithamkoor (Anglicized as Travancore) became the official name.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]-

Map of Travancore in 1871

-

A Canal scene in Travancore

The Kingdom of Travancore was located at the extreme southern tip of the Indian subcontinent. Geographically, Travancore was divided into three climatically distinct regions: the eastern highlands (rugged and cool mountainous terrain), the central midlands (rolling hills), and the western lowlands (coastal plains).[citation needed]

History

[edit]Due to the geographical isolation of the Malabar Coast from the rest of the Indian peninsula, attributed to the presence of the Western Ghats mountain ranges lying parallel to the coast, the population and language spoken in Kerala differed from those in neighboring states such as Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

According to the religious text "Keralolpathi" by the Nambudhiri Brahmins, the region from Gokharna to Kanyakumari district was created when Parashurama threw his axe and claimed this land, known as Parashuramakshetra.[15][16][17]

Medieval Kerala

[edit]

The Chera dynasty governed the Malabar Coast between Alappuzha in the south and Kasaragod in the north. The region around Coimbatore was ruled by the Cheras during the Sangam period roughly between the first and the fourth centuries CE and served as the eastern entrance to the Palakkad Gap, the principal trade route between the Malabar Coast and Tamil Nadu.[18] However the southern region of the present-day Kerala state was under the Ay dynasty. During the Ay dynasty, they spoke a language known as Middle Tamil,[19] Later Ay dynasty, conquered and succeeded by the Kulashekara Perumals,[20] based in Kollam (later known as Venad),[21] during the period of the Chera Kulashekara Perumal (Keralaputras) dynasty,[21] the language evolved into Old-Malayalam.[22] The Quilon copper plates (849/850 CE) are considered the oldest available inscription written in Old Malayalam.[23][24] Later, the northern regions of Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam, Alapuzha, and Pathanamthitta districts became proper Malayalam-speaking populations in Kerala, while the other districts showed influences from Arabic, Tamil and Kannada languages. During the period of Pattom Thanu Pillai, Travancore was referred to as Malayalam state or the land of proper Malayalis.[25][26][27]

Venad Swaroopam

[edit]

The former state of Venad at the tip of the Indian subcontinent, traditionally ruled by rajas known as the Venattadis. Until the end of the 11th century AD, it was a small principality in the Ay Kingdom. The Ays were the earliest ruling dynasty in southern Kerala, who, at their zenith, ruled over a region from Nagercoil in the south to Thiruvananthapuram in the north. Their capital during the first Sangam age was in Aykudi and later, towards the end of the eighth century AD, at Quilon (Kollam). Though a series of attacks by the resurgent Pandyas between the seventh and eighth centuries caused the decline of the Ays, the dynasty was powerful until the beginning of the tenth century.[28] Sulaiman al-Tajir, a Persian merchant who visited Kerala during the reign of Sthanu Ravi Varma (9th century CE), records that there was extensive trade between Kerala and China at that time, based at the port of Kollam.[29]

When the Ay diminished, Venad became the southernmost principality of the Second Chera Kingdom.[30] An invasion of the Cholas into Venad caused the destruction of Kollam in 1096. However, the Chera capital, Mahodayapuram, also fell in the subsequent Chola attack, which compelled the Chera king, Rama Varma Kulasekara, to shift his capital to Kollam.[31] Thus, Rama Varma Kulasekara, the last emperor of the Chera dynasty, was probably the founder of the Venad royal house, and the title of the Chera kings, Kulasekara, was thenceforth kept by the rulers of Venad. Thus the end of the Second Chera dynasty in the 12th century marks the independence of Venad.[32]

In the second half of the 12th century, two branches of the Ay dynasty, the Thrippappur and Chirava, merged in the Venad family, which set up the tradition of designating the ruler of Venad as Chirava Moopan and the heir-apparent as Thrippappur Moopan. While the Chrirava Moopan had his residence at Kollam, the Thrippappur Moopan resided at his palace in Thrippappur, nine miles north of Thiruvananthapuram, and was vested with authority over the temples of Venad kingdom, especially the Sri Padmanabhaswamy temple.[30]

Formation and development of Travancore

[edit]

In the early 18th century CE, the Travancore royal family adopted some members from the royal family of Kolathunadu based at Kannur, and Parappanad in present-day Malappuram district.[33] The history of Travancore began with Marthanda Varma, who inherited the kingdom of Venad (Thrippappur), and expanded it into Travancore during his reign (1729–1758). After defeating a union of feudal lords and establishing internal peace, he expanded the kingdom of Venad through a series of military campaigns from Kanyakumari in the south to the borders of Kochi in the north during his 29-year rule.[34] This rule also included Travancore-Dutch War (1739–1753) between Travancore and the Dutch East India Company, which had been allied to some of these kingdoms.[citation needed]

In 1741, Travancore won the Battle of Colachel against the Dutch East India Company, resulting in the complete eclipse of Dutch power in the region. In this battle, the Dutch Captain, Eustachius De Lannoy, was captured. He later defected to Travancore.[35]

De Lannoy was appointed captain of His Highness' bodyguard[35] and later Senior Admiral ("Valiya kappittan")[36] and modernised the Travancore army by introducing firearms and artillery.[35] From 1741 to 1758, De Lannoy remained in command of the Travancore forces and was involved in annexation of small principalities.[37]

Travancore became the most dominant state in the Kerala region by defeating the powerful Zamorin of Kozhikode in the battle of Purakkad in 1755.[36] Ramayyan Dalawa, the prime minister (1737–1756) of Marthanda Varma, also played an important role in this consolidation and expansion.

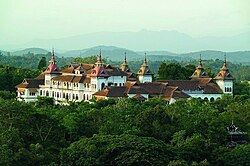

On 3 January 1750, (5 Makaram, 925 Kollavarsham), Marthanda Varma virtually "dedicated" Travancore to his tutelary deity Padmanabha, one of the aspects of the Hindu God Vishnu with a lotus issuing from his navel on which Brahma sits. From then on the rulers of Travancore ruled as the "servants of Padmanabha" (the Padmnabha-dasar).[38]

At the Battle of Ambalapuzha, Marthanda Varma defeated the union of the kings who had been deposed and the king of the Cochin kingdom.[citation needed]

Mysore invasion

[edit]

Marthanda Varma's successor Karthika Thirunal Rama Varma (1758–1798), who was popularly known as Dharma Raja, shifted the capital in 1795 from Padmanabhapuram to Thiruvananthapuram. Dharma Raja's period is considered a Golden Age in the history of Travancore. He not only retained the territorial gains of his predecessor, but also improved and encouraged social development. He was greatly assisted by a very efficient administrator, Raja Kesavadas, the Diwan of Travancore. [citation needed]

Travancore often allied with the English East India Company in military conflicts.[39] During Dharma Raja's reign, Tipu Sultan, the de facto ruler of Mysore and the son of Hyder Ali, attacked Travancore in 1789 as a part of the Mysore invasion of Kerala. Dharma Raja had earlier refused to hand over the Hindu political refugees from the Mysore occupation of Malabar who had been given asylum in Travancore. The Mysore army entered the Cochin kingdom from Coimbatore in November 1789 and reached Thrissur in December. On 28 December 1789 Tipu Sultan attacked the Nedunkotta (Northern Lines) from the north, causing the Battle of Nedumkotta (1789), and the defeat of the Mysore army.

Velu Thampi Dalawa's rebellion

[edit]

On Dharma Raja's death in 1798, Balarama Varma (1798–1810), the weakest ruler of the dynasty, took over at the age of sixteen. A treaty brought Travancore under a Subsidiary alliance with the East India Company in 1795.[39]

The Prime Ministers (Dalawas or Dewans) started to take control of the kingdom beginning with Velu Thampi Dalawa (Velayudhan Chempakaraman Thampi) (1799–1809) who was appointed as the divan following the dismissal of Jayanthan Sankaran Nampoothiri (1798–1799). Initially, Velayudhan Chempakaraman Thampi and the English East India Company got along very well. When a section of the Travancore army mutinied in 1805 against Velu Thampi Dalawa, he sought refuge with the British Resident Colonel (later General) Colin Macaulay and later used English East India Company troops to crush the mutiny. Velu Thampi also played a key role in negotiating a new treaty between Travancore and the English East India Company. However, the demands of the East India Company for the payment of compensation for their involvement in the Travancore-Mysore War (1791) on behalf of Travancore, led to tension between the Diwan and Colonel Macaulay. Velu Thampi and the diwan of Cochin kingdom, Paliath Achan Govindan Menon, who was unhappy with Macaulay for granting asylum to his enemy Kunhi Krishna Menon, declared "war" on the East India Company. [citation needed]

The East India Company army defeated Paliath Achan's army in Cochin on 27 February 1809. Paliath Achan surrendered to the East India Company and was exiled to Madras and later to Benaras. The Company defeated forces under Velu Thampi Dalawa at battles near Nagercoil and Kollam, and inflicted heavy casualties on the rebels, many of whom then deserted and went back home. The Maharajah of Travancore, who hitherto had not openly taken any part in the rebellion, now allied with the British and appointed one of Thampi's enemies as his prime minister. The allied East India Company army and the Travancore soldiers camped in Pappanamcode, just outside Thiruvananthapuram. Velu Thampi Dalawa now organised a guerrilla struggle against the company, but committed suicide to avoid capture by the Travancore army. After the mutiny of 1805 against Velu Thampi Dalawa, most of the Nair army battalions of Travancore were disbanded, and after Velu Thampi Dalawa's uprising, almost all of the remaining Travancore forces were also disbanded, with the East India Company undertaking to serve the Rajah in cases of external and internal aggression. [citation needed]

Cessation of mahādanams

[edit]The Rajahs of Travancore had been conditionally promoted to Kshatriyahood with periodic performance of 16 mahādānams (great gifts in charity) such as Hiranya-garbhā, Hiranya-Kāmadhenu, and Hiranyāswaratā in each of which thousands of Brahmins had been given costly gifts apart from each getting a minimum of 1 kazhanch (78.65 gm) of gold.[40] In 1848 the Marquess of Dalhousie, then Governor-General of India, was apprised that the depressed condition of the finances in Travancore was due to the mahādanams by the rulers.[41] Lord Dalhousie instructed Lord Harris, Governor of the Madras Presidency, to warn the then King of Travancore, Martanda Varma (Uttram Tirunal 1847–60), that if he did not put a stop to this practice, the Madras Presidency would take over his state's administration. This led to the cessation of the practice of mahādanams. [citation needed]

All Travancorean Kings including Sree Moolam Thirunal conducted the Hiranyagarbham and Tulapurushadaanam ceremonies. Maharaja Chithira Thirunal was the only King of Travancore not to have conducted these rituals as he considered them extremely costly.[42]

The 19th and early 20th centuries

[edit]

In Travancore, the caste system was more rigorously enforced than in many other parts of India up to the mid-1800s. The hierarchical caste order was deeply entrenched in the social system and was supported by the government, which transformed this caste-based social system into a religious institution.[43] In such a context, the belief in Ayyavazhi, apart from being a religious system, served also as a reform movement in uplifting the downtrodden of society, both socially and religiously. The rituals of Ayyavazhi constituted a social discourse. Its beliefs, mode of worship, and religious organisation seem to have enabled the Ayyavazhi group to negotiate, cope with, and resist the imposition of authority.[44] The hard tone of Vaikundar towards this was perceived as a revolution against the government.[45] So King Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma initially imprisoned Vaikundar in the Singarathoppu jail, where the jailor Appaguru ended up as a disciple of Vaikundar. Vaikundar was later set at liberty by the King.[46]

-

Travancore's postal service adopted a standard cast iron pillar box, made by Massey & Co in Madras, similar to the British Penfold model introduced in 1866. This Anchal post box is in Perumbavoor.

-

Ayilyam Thirunal of Travancore (centre) with the first prince (left) and Dewan Rajah Sir T. Madhava Rao (right)

-

The last King of Travancore, Sree Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma

-

Travancore Nair Brigade in 1861

After the death of Sree Moolam Thirunal in 1924, Sethu Lakshmi Bayi became regent (1924–1931), as the heir apparent, Sree Chithira Thirunal was then a minor, 12 years old.[47]

In 1935, Travancore joined the Indian State Forces Scheme and a Travancore unit was named 1st Travancore Nair Infantry, Travancore State Forces. The unit was reorganised as an Indian State Infantry Battalion by Lieutenant Colonel H S Steward, who was appointed commandant of the Travancore State Forces.[48]

The last ruling king of Travancore, Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, reigned from 1931 to 1949. "His reign marked revolutionary progress in the fields of education, defence, economy and society as a whole."[49] He made the famous Temple Entry Proclamation on 12 November 1936, which opened all the Kshetrams (Hindu temples in Kerala) in Travancore to backward communities. This act won him praise from across India, most notably from Mahatma Gandhi. The first public transport system (Thiruvananthapuram–Mavelikkara) and telecommunication system (Thiruvananthapuram Palace–Mavelikkara Palace) were launched during his reign. He also started the industrialisation of the state, enhancing the role of the public sector. He introduced heavy industry in the state and established giant public sector undertakings. As many as twenty industries were established, mostly for utilizing the local raw materials such as rubber, ceramics, and minerals. A majority of the premier industries in Kerala even today, were established by Sree Chithira Thirunal. He patronized musicians, artists, dancers, and Vedic scholars. Sree Chithira Thirunal appointed, for the first time, an Art Advisor to the Government, Dr. G. H. Cousins. He also established a new form of University Training Corps, viz. Labour Corps, preceding the N.C.C, in the educational institutions. The expenses of the university were to be met fully by the government. Sree Chithira Thirunal also built a beautiful palace named Kowdiar Palace, finished in 1934, which was previously an old Naluektu, given by Sree Moolam Thirunal to his mother Sethu Parvathi Bayi in 1915.[50][51][52]

A famine in 1943 claimed approximately 90,000 lives in Travancore.[53]

However, his prime minister, Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer, was unpopular among the communists of Travancore. The tension between the Communists and Iyer led to minor riots. In one such riot in Punnapra-Vayalar in 1946, the Communist rioters established their own government in the area. This was put down by the Travancore Army and Navy. The prime minister issued a statement in June 1947 that Travancore would remain an independent country instead of joining the Indian Union; subsequently, an attempt was made on his life, following which he resigned and left for Madras, to be succeeded by Sri P.G.N. Unnithan. According to witnesses such as K.Aiyappan Pillai, constitutional adviser to the Maharaja and historians like A. Sreedhara Menon, the rioters and mob-attacks had no bearing on the decision of the Maharaja.[54][55] After several rounds of discussion and negotiation between Sree Chithira Thirunal and V.P. Menon, the king agreed that the Kingdom should accede to the Indian Union on 12 August 1947.[56] On 1 July 1949 the Kingdom of Travancore was merged with the Kingdom of Cochin and the short-lived state of Travancore-Kochi was formed.[57]

On 11 July 1991, Maharaja Sree Chithira Thirunal suffered a stroke and was admitted to a hospital, where he died on 20 July. He had ruled Travancore for 67 years and at his death was one of the few surviving rulers of a first-class princely state in the old British Raj. He was also the last surviving Knight Grand Commander of both the Order of the Star of India and of the Order of the Indian Empire. He was succeeded as head of the Royal House as well as the Titular Maharajah of Travancore by his younger brother, Uthradom Thirunal Marthanda Varma. The Government of India issued a stamp on 6 Nov 1991, commemorating the reforms that marked his reign in Travancore.[58]

Formation of Kerala

[edit]The State of Kerala came into existence on 1 November 1956, with a governor appointed by the president of India as the head of state instead of a king.[59] The king was stripped of all political powers and of the right to receive privy purses, according to the twenty-sixth amendment of the Indian constitution act of 31 July 1971. He died on 20 July 1991.[60]

Merger of Kanyakumari with Madras State

[edit]Tamils lived in large numbers in the Thovalai, Agastheeswaram, Sengottai, Eraniel, Vilavancode, Kalkulam, Devikulam, Neyyattinkara, Thiruvananthapuram South and Thiruvananthapuram North taluks of erstwhile Travancore State.[5] In the Tamil regions, Malayalam was the official language and there were only a few Tamil schools. So the Tamils met many hardships. The Travancore state government continued rejecting the requests of Tamils.[61] During that period the Travancore State Congress favoured the idea of uniting all the Malayalam speaking regions and forming a "Unified Kerala". In protest against this idea, many Tamil leaders vacated the party. Tamils gathered together at Nagercoil on 16 December 1945 under the leadership of Sam Nathaniel and formed the new political party All Travancore Tamilian Congress. That party pushed for the merger of Tamil regions in Travancore with Tamil Nadu.[62] During the election campaign, clashes occurred between the Tamil Nadar community and the Malayali Nair community in Kalkulam – Vilavancode taluks. The police force suppressed the agitating Nadars. In February 1948 police opened fire and two Tamil-speaking Nadars were killed.[63]

In the working committee meeting of Tamilian congress at Eraviputhur on 30 June 1946, the name of the political party was changed to Travancore Tamil Nadu Congress (T.T.N.C). T.T.N.C was popular among the Tamils living in Thovalai and Agateeswaram taluks. Ma. Po. Sivagnanam (Ma.Po.Si) was the only leader from Tamil Nadu who acted in favour of T.T.N.C.[63] After the independence of India, State Assembly elections were announced in Travancore. As a consequence, T.T.N.C improved its popularity among Tamils. A popular and leading advocate from Vilavancode, A. Nesamony organised a meeting of his supporters at Allan Memorial Hall, Nagercoil on 8 September 1947. In that meeting it was declared that they must achieve their objective through their political organisation, the T.T.N.C. And T.T.N.C started gaining strength and momentum in Kalkulam – Vilavancode Taluks.[64]

T.T.N.C won in 14 constituencies in the election to the State Legislative Assembly. Mr. A. Nesamony was elected as the legislative leader of the party. Then under his leadership, the awakened Tamil population was prepared to undergo any sacrifice to achieve their goal.[65]

In 1950, a meeting was held at Palayamkottai to make compromises between state congress and T.T.N.C. The meeting met with failure and Mr. Sam Nathaniel resigned from the post of president of T.T.N.C Mr. P. Ramasamy Pillai, a strong follower of Mr. A. Nesamony was elected as the New President.[64] The first general election of Independent India was held on 1952. T.T.N.C won 8 legislative assembly seats. Mr. A. Chidambaranathan became the minister on behalf of T.T.N.C in the coalition state government formed by the Congress. In the parliamentary Constituency Mr. A. Nesamony was elected as M.P. and in the Rajyasabha seat. Mr. A. Abdul Razak was elected as M.P. on behalf of T.T.N.C.[64] In due course, accusing the Congress government for not showing enough care the struggle of the Tamils, T.T.N.C had broken away from the coalition and the Congress government lost the majority. So fresh elections were announced. In 1954 elections, T.T.N.C gained victory in 12 constituencies.[64] Pattom Thanu Pillai was the chief minister for Thiru – Kochi legislative assembly. He engaged hard measures against the agitations of Tamils. Especially the Tamils at Devikulam – Peermedu regions went through the atrocities of Travancore Police force. Condemning the attitude of the police, T.T.N.C leaders from Nagercoil went to Munnar and participated in agitations against the prohibitive orders. The leaders were arrested and an uncalm atmosphere prevailed in South Travancore.[66]

On 11 August, Liberation Day celebrations were held at many places in South Travancore. Public meetings and processions were organised. Communists also collaborated with the agitation programmes. Police opened fire at the processions in Thoduvetty (Martandam) and Puthukadai. Nine Tamil volunteers were killed and thousands of T.T.N.C and communist sympathizers were arrested in various parts of Tamil main land. At the end, Pattom Thanu Pillai's ministry was toppled and normalcy returned to the Tamil regions.[65] The central government had appointed Fazal Ali Commission(1953 dec) for the states reorganisation based on language. It submitted its report on 10 August 1955. Based on this report, Devikulam – Peermedu and Neyyattinkara Taluks were merged with Kerala state.[67] On 1 November 1956 – four Taluks Thovalai, Agastheeswaram, Kalkulam, Vilavancode were recognised to form the New Kanyakumari District and merged with Tamil Nadu State. Half of Sengottai Taluk was merged with Tirunelveli District. The main demand of T.T.N.C was to merger the Tamil regions with Tamil Nadu and major part of its demand was realised. So T.T.N.C was dissolved thereafter.[65]

Retainment of Devikulam and Peerumedu Taluks in Kerala

[edit]Apart from Kanyakumari district, the Taluks of Devikulam and Peermade in present-day Idukki district also had a Tamil-majority until late 1940's.[68] The T.T.N.C had also requested to merge these Taluks with Madras State.[68] However it was due to some decisions of Pattom Thanu Pillai, who was the first prime minister of Travancore, that they retained in the modern-state of Kerala.[68] Pattom came up with a colonisation project to re-engineer the demography of Cardamom Hills.[68] His colonisation project was to relocate 8,000 Malayalam-speaking families into the Taluks of Devikulam and Peermade.[68] About 50,000 acres in these Taluks, which were Tamil-majority area, were chosen for the colonisation project.[68] As a victory of the Colonisation project done by post-independence Travancore, these two Taluks and a larger portion of Cardamom Hills retained in the state of Kerala, after States Reorganisation Act, 1956.[68]

Politics

[edit]Under the direct control of the King, Travancore's administration was headed by a Dewan assisted by the Neetezhutthu Pillay or secretary, Rayasom Pillay (assistant or under-secretary) and a number of Rayasoms or clerks along with Kanakku Pillamars (accountants). Individual districts were run by Sarvadhikaris under the supervision of Diwan, while dealings with the neighbouring states and Europeans was under the purview of the Valia Sarvahi, who signed treaties and agreements.[69]

Rulers of Travancore

[edit]- Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma 1729–1758[70]

- Karthika Thirunal Rama Varma (Dharma Raja) – 1758–1798

- Balarama Varma I – 1798–1810

- Gowri Lakshmi Bayi – 1810–1815 (Queen from 1810 to 1813 and Regent Queen from 1813 to 1815)

- Gowri Parvati Bayi (Regent) – 1815–1829

- Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma III – 1813–1846

- Uthram Thirunal Marthanda Varma II – 1846–1860

- Ayilyam Thirunal Rama Varma III – 1860–1880

- Visakham Thirunal Rama Varma IV – 1880–1885

- Sree Moolam Thirunal Rama Varma VI – 1885–1924

- Sethu Lakshmi Bayi (Regent) – 1924–1931

- Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma II – 1924–1949 / died 1991

Titular Maharajahs of Travancore since 1991

[edit]- Uthradom Thirunal Marthanda Varma III – 1991–2013.

- Moolam Thirunal Rama Varma VI – Since 2013.

His heir is Revathi Thirunal Balagopal Varma – the titular Elayaraja (Crown Prince) (born 1953).

Prime Ministers of Travancore

[edit]Dalawas

[edit]- Arumukham Pillai 1729–1736[citation needed]

- Thanu Pillai 1736–1737

- Ramayyan Dalawa 1737–1756

- Martanda Pillai 1756–1763

- Warkala Subbayyan 1763–1768

- Krishna Gopalayyan 1768–1776

- Vadiswaran Subbrahmanya Iyer 1776–1780

- Mullen Chempakaraman Pillai 1780–1782

- Nagercoil Ramayyan 1782–1788

- Krishnan Chempakaraman 1788–1789

- Raja Kesavadas 1789–1798

- Odiery Jayanthan Sankaran Nampoothiri 1798–1799

- Velu Thampi Dalawa 1799–1809

- Oommini Thampi 1809–1811

Dewans

[edit]

- Col. John Munro 1811–1814[citation needed]

- Devan Padmanabhan Menon 1814–1814

- Bappu Rao (acting) 1814–1815

- Sanku Annavi Pillai 1815–1815

- Raman Menon 1815–1817

- Reddy Row 1817–1821

- T. Venkata Rao 1821–1830

- Thanjavur Subha Rao 1830–1837

- T. Ranga Rao (acting) 1837–1838

- T. Venkata Rao (Again) 1838–1839

- Thanjavur Subha Rao (again) 1839–1842

- Krishna Rao (acting) 1842–1843

- Reddy Row (again) 1843–1845

- Srinivasa Rao (acting) 1845–1846

- Krishna Rao 1846–1858

| Name | Portrait | Took office | Left office | Term[71] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. Madhava Rao |

|

1857 | 1872 | 1 |

| A. Seshayya Sastri |

|

1872 | 1877 | 1 |

| Nanoo Pillai | 1877 | 1880 | 1 | |

| V. Ramiengar |

|

1880 | 1887 | 1 |

| T. Rama Rao |

|

1887 | 1892 | 1 |

| S. Shungrasoobyer |

|

1892 | 1898 | 1 |

| V. Nagam Aiya |

|

1901 | 1904 | 1 |

| K. Krishnaswamy Rao |

|

1898 | 1904 | 1 |

| V. P. Madhava Rao |

|

1904 | 1906 | 1 |

| S. Gopalachari |

|

1906 | 1907 | 1 |

| P. Rajagopalachari | 1907 | 1914 | 1 | |

| M. Krishnan Nair | 1914 | 1920 | 1 | |

| T. Raghavaiah | 1920 | 1925 | 1 | |

| M. E. Watts | 1925 | 1929 | 1 | |

| V. S. Subramanya Iyer | 1929 | 1932 | 1 | |

| T. Austin | 1932 | 1934 | 1 | |

| Sir Muhammad Habibullah |

|

1934 | 1936 | 1 |

| Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer |

|

1936 | 1947 | 1 |

| P. G. N. Unnithan | 1947 | 1947 | 1 |

Prime Ministers of Travancore (1948–49)

[edit]| No.[a] | Name | Portrait | Term of office[72][73] (tenure length) |

Assembly (election) |

Appointed by

(Monarch) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | Days in office | |||||||

| 1 | Pattom A. Thanu Pillai |

|

24 March 1948 | 17 October 1948 | 210 days | Indian National Congress | Representative

Body (1948–49) |

Sir Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, Maharaja of Travancore | |

| 2 | Paravoor T. K. Narayana Pillai | 22 October 1948 | 1 July 1949 | 253 days | |||||

Administrative divisions

[edit]In 1856, the princely state was sub-divided into three divisions, each of which was administered by a Divan Peishkar, with a rank equivalent to a District Collector in British India.[74] These were the:

- Northern Travancore (Cottayam) comprising the talukas of Sharetalay, Vycome, Yetmanoor, Cottayam, Chunginacherry, Meenachil, Thodupolay, Moovatupolay, Kunnathnaud, Alangaud and Paravoor;

- Quilon (Central Travancore), comprising the talukas of Quilon, Amabalapulay, Chengannoor, Pandalam, Kunnattur, Karungapully, Kartikapully, Harippad and Mavelikaray

- Southern Travancore (Padmanabhapuram) comprising Thiruvananthapuram, Chirayinkir, Thovalay, Auguteeswarom, Kalculam, Eraneel, and Velavencode.

Divisions according to the 1911 Census of Travancore

[edit]1. Padmanabhapuram Division

[edit]The 1911 Census Report of Travancore states that Padmanabhapuram Division was the original seat of Travancore, where Thiruvithamcode and Padmanabhapuram are located.[4] The report further states that a vast majority of this division was ethnic Tamils.[4] Padamanabhapuram Division consisted of the present-day district of Kanyakumari in Tamil Nadu.[4] The report also states that the two southernmost Taluks of this division, namely Thovalai and Agastheeswaram, geographically too more resembles to Pandya Nadu of Tamil country and the eastern Coromandel Coast of the Madras Presidency than the rest of Malayalam country.[4]

2. Thiruvananthapuram Division

[edit]It was the headquarters of Travancore since 1795.[4] The Neyyattinkara taluk was a main seat of industry according the 1911 census report of Travancore.[4] This division also contained many ethnic Tamils, mostly concentrated in the southern Taluks of Neyyattinkara and Thiruvananthapuram.[4] The Trivandrum Division consisted of the present-day Thiruvananthapuram district excluding the British colony at Anchuthengu.[4]

3. Quilon Division

[edit]Quilon was the capital of Venad and the largest port town in Travancore, and was also one of the oldest ports on Malabar Coast.[4] The 1911 Census of Travancore states that it was from Quilon division onwards that the genuine country of Malayalam starts.[4] However, the Sengottai taluk of this division which was earlier under Kottarakkara Thampuran, was a Tamil-majority region.[4] Geographically too Sengottai resembled to Madurai and Pandya Nadu than rest of the Malayalam country.[4] The Quilon division encompassed present-day Kollam district, Pathanamthitta district, Alappuzha district and some parts of Kottayam district.

4. Kottayam Division

[edit]It was situated in the northernmost area of Travancore.[4] It was a pure Malayalam-speaking and geographical region.[4] The Vembanad Lake was a speciality of this division.[4]

5. Devikulam Division

[edit]It consisted most of the present-day Idukki district.[4] It was also related to Pandya Nadu and Kongu Nadu.[4] Devikulam division was Tamil-speaking region.[4]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1816 | 906,587 | — |

| 1836 | 1,280,668 | +1.74% |

| 1854 | 1,262,647 | −0.08% |

| 1875 | 2,311,379 | +2.92% |

| 1881 | 2,401,158 | +0.64% |

| 1891 | 2,557,736 | +0.63% |

| 1901 | 2,952,157 | +1.44% |

| 1911 | 3,428,975 | +1.51% |

| 1921 | 4,006,062 | +1.57% |

| 1931 | 5,095,973 | +2.44% |

| 1941 | 6,070,018 | +1.76% |

| Source:[75][76][77] | ||

- Hinduism (60.5%)

- Christianity (32.35%)

- Islam (7.15%)

Travancore had a population of 6,070,018 at the time of the 1941 Census of India.[1]

Religions

[edit]| Census year | Total population | Hindus | Christians | Muslims | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1816 – 1820 | 906,587[79] | 752,371[79] | 82.99% | 112,158[79] | 12.37% | 42,058[79] | 4.64% |

| 1881 | 2,401,158[5] | 1,755,610[5] | 73.12% | 498,542[5] | 20.76% | 146,909[5] | 6.12% |

| 1891 | 2,557,736[80] | 1,871,864[80] | 73.18% | 526,911[80] | 20.60% | 158,823[80] | 6.21% |

| 1901 | 2,952,157[79] | 2,063,798[79] | 69.91% | 697,387[79] | 23.62% | 190,566[79] | 6.46% |

| 1911 | 3,428,975[79] | 2,298,390[79] | 67.03% | 903,868[79] | 26.36% | 226,617[79] | 6.61% |

| 1921 | 4,006,062[79] | 2,562,301[79] | 63.96% | 1,172,934[79] | 29.27% | 270,478[79] | 6.75% |

| 1931 | 5,095,973[79] | 3,137,795[79] | 61.57% | 1,604,475[79] | 31.46% | 353,274[79] | 6.93% |

| 1941 | 6,070,018[78] | 3,671,480[78] | 60.49% | 1,963,808[78] | 32.35% | 434,150[78] | 7.15% |

Languages

[edit]| Census year | Total population | Malayalam | Tamil | Others | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1875 | 2,311,379[5] | 1,902,533[5] | 82.32% | 387,909[5] | 16.78% | 20,937[5] | 0.91% |

| 1881 | 2,401,158[5] | 1,937,454[5] | 80.69% | 439,565[5] | 18.31% | 24,139[5] | 1.01% |

| 1891 | 2,557,736[80] | 2,079,271[80] | 81.29% | 448,322[80] | 17.53% | 30,143[80] | 1.18% |

| 1901 | 2,952,157[81] | 2,420,049[81] | 81.98% | 492,273[81] | 16.68% | 39,835[81] | 1.35% |

| 1911 | 3,428,975[82] | 2,836,728[82] | 82.73% | 554,618[82] | 16.17% | 37,629[82] | 1.10% |

| 1921 | 4,006,062[83] | 3,349,776[83] | 83.62% | 624,917[83] | 15.60% | 31,369[83] | 0.78% |

| 1931 | 5,095,973[79] | 4,260,860[79] | 83.61% | 788,455[79] | 15.47% | 46,658[79] | 0.92% |

| Name of Division[5] | Malayalam (%)[5] | Tamil (%)[5] |

| Padmanabhapuram Division | 11.24[5] | 88.03[5] |

|---|---|---|

| Thiruvananthapuram Division | 87.05[5] | 12.09[5] |

| Quilon Division | 92.42[5] | 6.55[5] |

| Cottayam Division | 95.19[5] | 3.65[5] |

| Devicolam Division | 36.18[5] | 59.14[5] |

| Name of Taluk[5] | Total population[5] | Malayalam[5] | Tamil[5] | Others[5] | ||||

| 1 | Thovalai | 30,260[5] | 190[5] | 0.63% | 29,708[5] | 98.18% | 362[5] | 1.20% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Agasteeswaram | 78,979[5] | 705[5] | 0.89% | 76,645[5] | 97.04% | 1,629[5] | 2.06% |

| 3 | Eraniel | 112,116[5] | 9,640[5] | 8.60% | 102,389[5] | 91.32% | 87[5] | 0.08% |

| 4 | Culcoolum | 60,908[5] | 10,528[5] | 17.29% | 49,930[5] | 81.98% | 450[5] | 0.74% |

| 5 | Vilavancode | 69,688[5] | 18,497[5] | 26.54% | 51,172[5] | 73.43% | 19[5] | 0.03% |

| 6 | Neyyattinkarai | 110,410[5] | 97,485[5] | 88.29% | 12,809[5] | 11.60% | 116[5] | 0.11% |

| 7 | Thiruvananthapuram South | 51,337[5] | 39,711[5] | 77.35% | 10,522[5] | 20.50% | 1,104[5] | 2.15% |

| 8 | Thiruvananthapuram North | 51,649[5] | 38,979[5] | 75.47% | 11,102[5] | 21.50% | 1,568[5] | 3.04% |

| 9 | Nedoomangad | 52,211[5] | 48,492[5] | 92.88% | 3,573[5] | 6.84% | 146[5] | 0.28% |

| 10 | Sheraingil | 87,072[5] | 82,339[5] | 94.56% | 4,629[5] | 5.37% | 146[5] | 0.17% |

| 11 | Kottarakkarai | 55,924[5] | 51,836[5] | 94.56% | 3,994[5] | 7.14% | 94[5] | 0.17% |

| 12 | Pathanapuram | 37,064[5] | 35,264[5] | 95.14% | 1,603[5] | 4.32% | 197[5] | 0.53% |

| 13 | Sengottai | 30,477[5] | 7[5] | 0.02% | 29,694[5] | 97.43% | 776[5] | 2.55% |

| 14 | Quilon | 108,469[5] | 103,775[5] | 95.67% | 3,650[5] | 3.37% | 1,044[5] | 0.96% |

| 15 | Kunnathur | 62,700[5] | 60,330[5] | 96.22% | 2,339[5] | 3.73% | 31[5] | 0.05% |

| 16 | Karunagapully | 101,039[5] | 99,079[5] | 98.06% | 1,814[5] | 1.80% | 146[5] | 0.14% |

| 17 | Karthikapully | 81,969[5] | 79,705[5] | 97.24% | 1,059[5] | 1.29% | 1,205[5] | 1.47% |

| 18 | Mavelikkarai | 111,731[5] | 107,404[5] | 96.13% | 4,139[5] | 3.70% | 188[5] | 0.17% |

| 19 | Chengannur | 81,301[5] | 80,295[5] | 98.76% | 986[5] | 1.21% | 20[5] | 0.02% |

| 20 | Thiruvallai | 103,007[5] | 101,041[5] | 98.09% | 1,664[5] | 1.62% | 302[5] | 0.29% |

| 21 | Ambalappulay | 93,401[5] | 82,345[5] | 88.16% | 5,864[5] | 6.28% | 5,192[5] | 5.56% |

| 22 | Sharetala | 113,704[5] | 107,108[5] | 94.20% | 2,312[5] | 2.03% | 4,284[5] | 3.77% |

| 23 | Vycome | 76,414[5] | 72,827[5] | 95.31% | 2,684[5] | 3.51% | 903[5] | 1.81% |

| 24 | Yettoomanoor | 79,058[5] | 75,004[5] | 94.87% | 3,879[5] | 4.91% | 175[5] | 0.22% |

| 25 | Cottayam | 64,958[5] | 63,831[5] | 98.27% | 722[5] | 1.11% | 405[5] | 0.62% |

| 26 | Chunganacherry | 74,154[5] | 66,481[5] | 89.65% | 7,394[5] | 9.97% | 279[5] | 0.38% |

| 27 | Meenachel | 57,102[5] | 55,186[5] | 96.64% | 1,857[5] | 3.25% | 59[5] | 0.10% |

| 28 | Moovattupulay | 95,460[5] | 93,473[5] | 97.92% | 1,930[5] | 2.02% | 57[5] | 0.06% |

| 29 | Todupulay | 24,321[5] | 23,227[5] | 95.50% | 1,085[5] | 4.46% | 9[5] | 0.04% |

| 30 | Cunnathunad | 109,625[5] | 108,083[5] | 98.59% | 831[5] | 0.76% | 711[5] | 0.65% |

| 31 | Alangaud | 66,753[5] | 65,839[5] | 98.63% | 571[5] | 0.86% | 343[5] | 0.51% |

| 32 | Paravoor | 61,966[5] | 56,495[5] | 91.17% | 3,332[5] | 5.38% | 2,139[5] | 3.45% |

| 33 | Cardamom Hills | 6,228[5] | 2,253[5] | 36.18% | 3,683[5] | 59.14% | 292[5] | 4.69% |

| - | Travancore | 2,401,158[5] | 1,937,454[5] | 80.69% | 439,565[5] | 18.31% | 24,139[5] | 1.01% |

Currency

[edit]Unlike the rest of India, Travancore divided the rupee into unique values, as represented on coins and stamps, as follows:

| Unit | Equivalent Sub-units |

|---|---|

| 1 Travancore Rupee | 7 Fanams |

| 1 Fanam | 4 Chuckrams |

| 1 Chuckram | 16 Cash |

Cash and Chuckram coins are copper. Travancore Fanam and Travancore Rupee coins are silver.

Culture

[edit]

Travancore was characterised by the popularity of its rulers among their subjects.[84] The Kings of Travancore, unlike their counterparts in the other princely states of India, spent only a small portion of their state's resources for personal use. This was in sharp contrast with some of the northern Indian kings. Since they spent most of the state's revenue for the benefit of the public, they were naturally much loved by their subjects.[85]

Violence rooted in religion or caste was uncommon in Travancore, but the barriers based on these parameters were rigid. Swami Vivekananda described Travancore as The Lunatic Asylum in India due to the level of caste discrimination.[86] Vaikom Satyagraha point out the high-level casteism existed in Travancore.

Travancore was once a dominant feudal state during the Venad period, with the Nair aristocracy reaching its peak compared to other kingdoms.[9] Later Nairs and Tamil Brahmins alone dominated the bureaucracy until the early 20th century. Many political ideologies (such as communism) and social reforms were not welcomed in Travancore, and in Punnapra, communist protesters were fired at. The Travancorean royal family are devout Hindus. Some practiced untouchability with British officers, European aristocrats and diplomats (for instance, Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 3rd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, has reported that Maharaja Visakham Thirunal had to take bath after touching Richard's wife, to remove ritual pollution, when they visited in 1880). The decline of the caste system began at the end of the 19th century due to a series of reformation movements. As a result, the Kingdom of Travancore became the region with the highest male literacy rate in India.[87]

Unlike most of India, In South Canara and Travancore (and the rest of Kerala), the social status and freedom of women who belong to forward castes were relatively high. However, the Upper cloth revolt of 19th century is an exception to this. The women of backward castes had not the permission to wear upper cloth in Travancore.[86] In some communities, the daughters inherited the property (though property was exclusively administered by men, their brothers) (until 1925), were educated, and had the right to divorce and remarry, but due to laws passed starting from 1925, by regent queen Sethu Lakshmi Bayi proper patriarchy was established and now women have relatively little rights.[88]

Notable people

[edit]- Paremmakkal Thoma Kathanar (1736–1799) is the author of Varthamanappusthakam (1790), the first ever travelogue in an Indian language.

- Mor Severios ( 1851–1927), Metropolitan

- Kandathil Varghese Mappillai (1857 – 6 July 1904) an Indian journalist, translator, publisher and the founder of the newspaper Malayala Manorama and the magazine Bhashaposhini.

See also

[edit]- Zamorin of Calicut

- Kingdom of Cochin

- Marthanda Varma

- Travancore-Cochin

- Thachudaya Kaimal

- Battle of Colachel

- Travancore War

- Travancore rupee

- Battle of Nedumkotta

- Cochin - Travancore Alliance (1761)

- Cochin Travancore War (1755–1756)

- Kingdom of Mysore

- Upper cloth revolt

- Vaikom Satyagraha

- Temple Entry Proclamation

- Merger of Kanyakumari with Madras State

- Madras Presidency

- Malabar District

- Marthandavarma (novel)

- The Years of Rice and Salt, an acclaimed novel that features an alternate history Travancore

Notes

[edit]- ^ A parenthetical number indicates that the incumbent has previously held office.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "Table 1 – Area, houses and population". 1941 Census of India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ British Archives http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/rd/d3e53001-d49e-4d4d-bcb2-9f8daaffe2e0

- ^ Census of India, 1901. 1903.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Iyer, A. Subrahmanya (1912). Census of India, 1911, Volume XXIII, TRAVANCORE, Part-I, Report (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of Travancore. pp. 19–22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck cl cm cn co cp cq cr cs ct cu cv cw cx cy cz da db dc dd de df dg dh di dj dk dl dm dn do dp dq dr ds dt du dv dw dx dy dz ea eb ec ed ee ef eg eh ei ej ek el em en eo ep eq er es et eu ev ew ex ey ez fa fb fc fd fe ff fg fh fi fj fk fl fm fn fo Report on the Census of Travancore (1881) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of India. 1884. pp. 135, 258.

- ^ Sanjeev Sanyal (10 August 2016). The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-93-86057-61-7.

- ^ "Travancore and the friendship alliance with the British and its consequences" (PDF). International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research. 8 (2): 90–91. ISSN 2455-2070.

- ^ Nair, T. P. Sankarankutty (13 February 1978). "A New Look on Travancore Revolt". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 39: 627–633. JSTOR 44139406.

- ^ a b P. Shungunny Menon (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Thiruvananthapuram: Higginbotham's.

- ^ R. Narayana Panikkar (1933). Travancore History (in Malayalam). Nagar Kovil.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Database: Handbook For India, Part 1 – Madras". 1 August 2008. p. vii. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "തിരുവിതാംകൂര്" (in Malayalam). The State Institute of Encyclopaedic Publications. 4 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004). The Indian Princes and their States. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-13944-908-3.

- ^ Mateer, Samuel (1871). The Land of Charity. University of Michigan Libraries. p. 160.

- ^ Gomantak Prakruti ani Sanskruti Part 1, p. 206, B. D. Satoskar, Shubhada Publication

- ^ Aiya VN (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. pp. 210–212. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ Ancient Indian History By Madhavan Arjunan Pillai, p. 204 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Subramanian, T. S (28 January 2007). "Roman connection in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ^ Ponvannan, Gayathri (2022). 100 Great Chronicles of Indian History: From Cave Paintings to the Constitution. Hachette India. ISBN 978-93-91028-77-0.

- ^ Lannoy, Mark de (1997). The Kulasekhara Perumals of Travancore: History and State Formation in Travancore from 1671 to 1758. Leiden University. ISBN 978-90-73782-92-1.

- ^ a b Menon, P. Shungoonny (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Higginbotham.

- ^ Sekhar, Anantaramayyar Chandra (1953). Evolution of Malayalam. S.M. Katre.

- ^ "Dravidian languages – History, Grammar, Map, & Facts". Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Narayanan, M. G. S. (2013) [1972]. Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks. ISBN 9788188765072. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (2011). Kerala History and its Makers. D C Books. ISBN 978-81-264-3782-5.

- ^ Liberation of the Oppressed a Continuous Struggle. History Kanyakumari District.

- ^ State), Travancore (Princely; Aiya, V. Nagam (1906). The Travancore State Manual. Travancore government Press.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Menon, A. Shreedhara (2016). India Charitram. Kottayam: DC Books. p. 219. ISBN 9788126419395.

- ^ a b A Sreedhara Menon (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 139. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ A Sreedhara Menon (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. p. 141. ISBN 978-81-264-1578-6. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ Travancore State Manual

- ^ C. J. Fuller (1976). The Nayars Today. CUP Archive. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-29091-3. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 136–140. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ a b Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "9 Madras : A Tale of 'Terrors'". Sainik Samachar. The journal of India's Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. p. 171. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Travancore." Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2011. [page needed][ISBN missing]

- ^ A Social History of India – Ashish Publishing House: ISBN 81-7648-170-X (2000). [page needed]

- ^ Sadasivan, S.N., 1988, Administration and social development in Kerala: A study in administrative sociology, New Delhi, Indian Institute of Public Administration

- ^ "ഹിരണ്യഗര്ഭച്ചടങ്ങിന് ഡച്ചുകാരോട് ചോദിച്ചത് 10,000 കഴിഞ്ച് സ്വര്ണം KERALAM Paramparyam - Mathrubhumi Special". Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014. MATHRUBHUMI Paramparyam ഹിരണ്യഗര്ഭച്ചടങ്ങിന് ഡച്ചുകാരോട് ചോദിച്ചത് 10,000 കഴിഞ്ച് സ്വര്ണം – "ശ്രീമൂലംതിരുനാള് വരെയുള്ള രാജാക്കന്മാര് ഹിരണ്യഗര്ഭം നടത്തിയിട്ടുണ്ടെന്നാണ് അറിയുന്നത്. ഭാരിച്ച ചെലവ് കണക്കിലെടുത്ത് ശ്രീചിത്തിരതിരുനാള് ബാലരാമവര്മ്മ മഹാരാജാവ് ഈ ചടങ്ങ് നടത്തിയില്ല."

- ^ Cf. Ward & Conner, Geographical and Statistical Memoir, p. 133; V. Nagam Aiya, The Travancore State Manual, Volume 2, Madras: AES, 1989 (1906), p. 72.

- ^ G. Patrick, Religion and Subaltern Agency, University of Madras, 2003, The Subaltern Agency in Ayyavali, p. 174.

- ^ "Kerala State Syllabus – Text books". Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.Towards Modern Kerala, 10th Standard Text Book, Chapter 9, p. 101.

- ^ C.f. Rev.Samuel Zechariah, The London Missionary Society in South Travancore, p. 201.

- ^ A. Sreedhara, Menon. A Survey of Kerala History. pp. 271–273.

- ^ "Travancore State Forces". 13 April 2020. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "During his rule, the revenues of the State were nearly quadrupled from a little over Rs 21/2 crore to over Rs 91/2 crore." – 'The Story of the Integration of the Indian States' by V. P. Menon

- ^ Supreme Court, Of India. "Good Governance: Judiciary and the Rule of Law" (PDF). Sree Chithira Thirunal Memorial Lecture, 29 December 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Gauri Lakshmi Bai, Aswathy Thirunal (1998). Sree Padmanabhaswamy Kshetram. Thiruvananthapuram: The State Institute of Languages, Kerala. pp. 242–243. ISBN 978-81-7638-028-7.

- ^ Menon, A. Sreedhara (1967). A Survey of Kerala History. Kottayam: D C Books. p. 273. ISBN 81-264-1578-9.

- ^ Balasubramanian, Aditya (2023). "A forgotten famine of '43? Travancore's muffled 'cry of distress'". Modern Asian Studies. 57 (5): 1495–1529. doi:10.1017/S0026749X21000706. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 259440543.

- ^ Sreedhara Menon in Triumph & Tragedy in Travancore Annals of Sir C. P.'s Sixteen Years, DC Books publication

- ^ Aiyappan Pillai Interview to Asianet news Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iIMS_6Z_WRE

- ^ "Instrument of Accession of His Highness the Maharajah of Travancore". Travancore State – Instrument of Accession and Standstill Agreement signed between Rama Verma, Ruler of Travancore State and the Dominion of India. New Delhi: Ministry of States, Government of India. 1947. p. 3. Retrieved 31 August 2022 – via National Archives of India.

- ^ Kurian, Nimi (30 June 2016). "Joining hands". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Gauri Lakshmi Bai, Aswathy Thirunal (1998). Sree Padmanabha Swamy Kshetram. Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala: The State Institute of Languages. pp. 278–282, 242–243, 250–251. ISBN 978-81-7638-028-7.

- ^ "The States Reorganisation Act, 1956" (PDF). legislative.gov.in. Government of India.

- ^ "The Constitution (Twenty-Sixth Amendment Act), 1971". Archived from the original on 6 December 2011.

- ^ V. S. Sathianesan – Tamil Separatism in Travancore

- ^ R. Isaac Jeyadhas – Kanyakumari District and Indian Independence Struggle (Tamil)

- ^ a b D. Daniel – Travancore Tamils: Struggle for Identity.

- ^ a b c d B. Yogeeswaran – History of Travancore Tamil Struggle (Tamil)

- ^ a b c D. Peter – Malayali Dominance and Tamil Liberation (Tamil)

- ^ R. Kuppusamy – Historical foot prints of a True War (Tamil)

- ^ B. Mariya John – Linguistic Reorganisation of Madras Presidenty

- ^ a b c d e f g Ayyappan, R (31 October 2020). "Why did Kerala surrender Kanyakumari without a fight?". Onmanorama. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ Aiya 1906, pp. 329–330.

- ^ de Vries, Hubert (26 October 2009). "Travancore". Hubert Herald. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012.

- ^ The ordinal number of the term being served by the person specified in the row in the corresponding period

- ^ Responsible Governments (1947–56). Kerala Legislature. Retrieved on 22 April 2014.

- ^ History of Kerala Legislature. Government of Kerala. Archived on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. p. 486. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Travancore, Part I, Vol-XXV (1941) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. 1942. p. 13.

- ^ Report on the Census of Travancore (1891) (PDF). Chennai: Government of India. 1894. p. 631.

- ^ Report on the Census of Travancore (1881) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of India. 1884. p. 87.

- ^ a b c d e Travancore, Part I, Vol-XXV (1941) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. 1942. pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Census of India, 1931, VOLUME XXVIII, Travancore, Part-I Report (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. 1932. pp. 327, 331.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Report on the Census of Travancore (1891) (PDF). Chennai: Government of India. 1894. pp. 10–11, 683.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, N. Subrahmanya (1903). Census of India-1901, Volume-XXVI, Travancore (Part-I). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. pp. 224–225.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, N. Subramhanya (1912). Census of India – 1911, Volume-XXIII, Travancore (Part-I) (PDF). Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Iyer, S. Krishnamoorthi (1922). Census of India, 1921, Volume-XXV, Travancore. Thiruvananthapuram: Government of Travancore. p. 91.

- ^ THE HINDU by STAFF REPORTER, 14 May 2013, 'Simplicity hallmark of Travancore royal family'- National seminar on the last phase of monarchy in Travancore inaugurated: "History is replete with instances where the Travancore royal family functioned more as servants of the State than rulers who exploited the masses. The simplicity that the family consistently upheld in all aspects of governance distinguished it from other contemporary monarchies, said Governor of West Bengal M.K. Narayanan"

- ^ "Sree Chithira Thirunal, was a noble model of humility, simplicity, piety and total dedication to the welfare of the people. In the late 19th and early 20th century when many native rulers were callously squandering the resources of their, states, this young Maharaja was able to shine like a solitary star in the firmament, with his royal dignity, transparent sincerity, commendable intelligence and a strong sense of duty."- 'A Magna Carta of Religious Freedom' Speech By His Excellency V.Rachaiya, Governor of Kerala, delivered at Kanakakkunnu Palace on 25.10.1992

- ^ a b A Survey of Kerala History, A. Shreedhara Menon (2007), DC Books, Kottayam

- ^ Jeffrey, Robin (1976). The decline of Nayar dominance : society and politics in Travancore, 1847-1908. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Santhanam, Kausalya (30 March 2003). "Royal vignettes: Travancore – Simplicity graces this House". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aiya, V. Nagam (1906). Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government Press. (Digital book format)

Further reading

[edit]- Hatch, Emily Gilchriest (1934). Pictures of Travancore. Oxford University Press. p. 64.

- Hatch, Emily Gilchriest (1933). Travancore: A guide book for the visitor with thirty-two illustrations and two maps. Calcutta: Oxford University Press. p. 270. (a second revision was published in 1939)

- Menon, P. Shungoonny (1879). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times. Higginbotham & Co., Madras.

- U. Sivaraman Nair (1955). Travancore–Cochin Language Handbook (1951) (PDF). Travancore–Cochin Government Press.

Census reports

[edit]- 1871 Travancore Census Report (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of Travancore. 1874.

- Report on the Census of Travancore (1881) (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of India. 1884.

- Report on the Census of Travancore (1891) (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of India. 1894.

- Iyer, N. Subrahmanya (1903). Census of India – 1901, Vol. XXVI, Travancore (Part I). Trivandrum: Government of Travancore.

- Iyer, N. Subramhanya (1912). Census of India – 1911, Vol. XXIII, Travancore (Part I) (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of Travancore.

- Iyer, S. Krishnamoorthi (1922). Census of India, 1921, Vol. XXV, Travancore. Trivandrum: Government of Travancore.

- Census of India, 1931, Vol. XXVIII, Travancore, Part I Report (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of Travancore. 1932.

- Travancore, Part I, Vol. XXV (1941) (PDF). Trivandrum: Government of Travancore. 1942.

External links

[edit]- Travancore State Manual by T.K.Velu Pillai (archived 7 May 2006)

- Kingdom of Travancore

- History of Kollam

- 1729 establishments in India

- 1949 disestablishments in India

- Feudal states of Kerala

- Historical Indian regions

- Kingdoms of Kerala

- Princely states of India

- Former British colonies and protectorates in Asia

- Travancore–Cochin

- Hindu states

- Gun salute princely states

- Former kingdoms

![Sree Padmanabha Swamy was the national deity of the Kingdom of Travancore.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/78/Sree_Padmanabha_Swamy_Temple.jpg/250px-Sree_Padmanabha_Swamy_Temple.jpg)