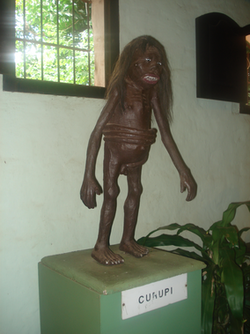

Kurupi

Curupi (Curupí) or Kurupi is a figure in Guaraní mythology, known particularly for an elongated penis that can wind once or several turns around the waist or torso, or wrap around its arms, and feared as the abductor and rapist of women.

He is one of the seven monstrous children of Tau and Kerana, and as such is one of the central legendary figures in the region of Guaraní speaking cultures.[1] He is also one of the few figures still prominent in the modern culture of the region.

Myths

[edit]

Kurupi is said to be somewhat similar in appearance to another, more popular figure from Guaraní mythology, the Pombero. Like the Pombero, Kurupi is said to be short, ugly, and hairy. He makes his home in the wild forests of the region, and was considered to be the lord of the forests and protector of wild animals.

Elongated phallus

[edit]Curupí's most distinctive feature was that his "[male] member was so deformed it [could wrap] once around the waist and reach [the front]", as attested by the traveler Aguirre in 1793.[3]

While the long penis feature and identification as a fertility symbol[5] is ubiquitous in written sources,[6] only a small percentage of Guaraní informants elocuted to the Curupí being equipped with such "a long penis which he can twine around his arm", according to a 1977 statistical study by Martha Blache.[7][a]

According to poet Eloy Fariña Nuñez (1926) the Curupí lassos or binds (enlazar) women with his elongated penis, and the women are able to make a getaway by cutting it off.[9]

On the authority of Fariña Nuñez, it is extrapolated that this penis must be long enough to wrap around the body several times.[10] Thus in the modern exaggerated telling, Kurupi's humongous penis winds several times around his waist like a belt.[11]

Abductor and rapist

[edit]Kurupi, one of seven monstrous siblings (cf. § Children of Tau and Kerana), is the kidnapper of women.[4] Much like the Pombero, Kurupi is often blamed for unexpected or unwanted pregnancies. His penis is said to be prehensile, and owing to its length he is supposed to be able to extend it through doors, windows, or other openings in a home and impregnate a sleeping woman without even having to enter the house. Together with the Pombero, Kurupi was a scapegoat used by adulterous women to avoid the wrath of their husbands, and by single women to explain their pregnancies, including in cases of rape. Children fathered by the Kurupi were expected to be small, ugly and hairy much like their father, and if male to inherit something of their father's virility. In some cases, Kurupi is blamed with the disappearance of young women, supposedly stealing them away to his home in the forest for use in satiating his libidinous desires (rape).

Parallels

[edit]The curupí may just be a sub-class of curupira, as it has been suggested that the name "Curupí" is merely a contraction of "Curú-piré" meaning "pimply-skinned" by Basílio de Magalhães (1928).[8]

The legend of Kurupi has faded somewhat in comparison to the Pombero, and figures more often as part of old tales. Rarely is he blamed with impregnating women anymore, although he is sometimes used to try and frighten young girls into being chaste.

Children of Tau and Kerana

[edit]According to Guaraní mythology Kurupi was one of seven offspring engendered by the evil spirit Tau who abducted Kerana, daughter of Marangatú and begot seven monstrous sietemesinos, i,e,, children born after only 7 months of gestation: Teju Jagua, Mbói Tu'ĩ, Moñái, most famously Jasy Jatere, then Kurupi, Ao Ao and the dog Luison.[4][12]

Curuzú-yeguá ritual

[edit]The creature Curupí is believed to be closely associated with the Guaraní ritual of the curuzú-yeguá (Guaraní: "adorned cross").[13] The notion that curuzú-yeguá originated as a pre-Christian ancient cult of Curupí was espoused by Goicoechea Menéndez and Natalicio González (1938?)[14] In the ritual, a cross is decorated with manioc flour bread called chipás. Enough is baked to go around to all attendees, who choose to eat breads of various shape like ladders and snakes. Paulo de Carvalho Neto psychoanalyzes these as phallic symbols, i.e., more modest representations of the Curupí which can take on a more overtly sexual form.[13]

Kurupi of the Guianas

[edit]There are also spirits called the Kurupi or Kulupi known to the Kaliña people of the Guianas, characterized by a large scrotum. It has a protruding forehead that prevents it from looking upward (cf. Cabeça de Cuia). It is hairy all over, with flowing long hair trailing behind; it has clawed fingers and toes, feet turned backward, and instead of buttocks has burning embers. The Kurupi roaming the forests noisily "kicks or knocks the tree buttresses".[15] (cf. curupira § Sounds and smell and sapopema). It can raise strong gusts of wind when angered and is considered the lord of winds by the Kaliña[15] (cf. saci)[b].

Goeje considered this Kurupi to be a cognate of the curupira of the Tupi people of Brazil, etc.[15] The Marana ywa among the Tenetehara is also said to be a cognate, as it is described as a small man with enormous testicles.[17]

Other phallic parallels

[edit]The Hebu spirits of the Warao people of Western Guayana also are said to be gifted with scrotal enormity.[18] The Ýoši spirit of the Selknam on Tierra del Fuego also have abnormally large phalluses,[19] while the Kamiri forest spirit of the Apurinã people have an penis only 1 centimeter long.[20]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ That is to say, of 26 respondents, only 16 (62%) even knew of the Curupí, and only two (8%) gave the long penis response. It is also noted "most informants who evinced a desire to disown their Indian heritage".[6]

- ^ Note that Basílio de Magalhães (1928)'s commentary on Curupí is placed under the section on "Sacy".[8]

References

[edit]- ^ "Mitologia". Archived from the original on 2007-05-12.

- ^ Carvalho Neto, Paulo de (1956). Folklore y psicoanálisis (in Spanish). Editorial Psique. p. 268.

- ^ Carvalho Neto (1956): "Curupí es aquella entidad mitológica cuyo 'miembro es tan disforme que alcanza en su pequeno cuerpo a dar una vuelta a la cintura', dice el viajero Aguirre, el año 1793".[2] citing his own yet unpublished Folklore del Paraguay (1961)

- ^ a b c Alvarez, Mario Rubén [in Spanish] (2002). Lo mejor del folklore paraguayo (in Spanish). Editorial El Lector. p. 61. ISBN 9789992560174.

- ^ e.g., Alvarez (2002): "Kurupi es el que tiene un falo que se lía por su cuerpo. Símbolo de la fecundidad y secuestrador de mujeres (Kurupi is the one with a phallus that wraps around his body. Symbol of fertility and kidnapper of women)".[4]

- ^ a b Blache (1977), p. 92.

- ^ Blache (1977), pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b c Magalhães, Basílio de [in Portuguese] (1928). "IV. Mythos Primarios, suas transformações e sobrevivencias : c) Sacy". O folcore no Brasil: com uma coletânea de 81 contos populares (in Portuguese). Braslia: Imprensa Nacional. p. 77. 1939 edition, p. 81

- ^ Fariña Nuñez (1926a) "Los mitos guaraníes". Revista do Instituto historico e geographico brasileiro. Tomo special: Congresso internacional de historia da America (1922), 2: 311–331", quoted by Basílio de Magalhães (1928)[8] reprinted Fariña Nuñez (1926b), p. 215.

- ^ >Montalto, Francisco Américo (1989). Panorama de la Realidad Histórica Del Río de la Plata Y Paraguay (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Asunción, Paraguay: Imprenta Cromos. p. 82.

Eloy Fariña Nuñez ([1926b], p. 215ff) lo describe con rasgos dionisíacos, caracterizado por un falo enorme que lo sujeta en varias vueltas al cuerpo y con el cual puede enlazar a las mujeres, especialmente a las niñas que se aventuran a penetrar solas en los montes.

- ^ "Personajes Mitológicos". Archived from the original on 2007-05-27.

- ^ Encina Ramos, Pedro (2005), Tau y Kerana- Escultura del Museo Mitológico (in Spanish), retrieved May 30, 2018

- ^ a b Carvalho Neto, Paulo de (1972). Folklore and Psychoanalysis. University of Miami Press. pp. 191–195. ISBN 9780870241673.

- ^ Cadogan (1961), p. 40 citing Carvalho Neto (1956), pp. 266–269. Earlier citing Natalicio González (1948) [1938?] Proceso y formación de la cultura paraguaya

- ^ a b c Goeje (1943), p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Zerries, Otto [in German] (1954). Wild- und Buschgeister in Südamerika: eine Untersuchung jägerzeitlicher Phänomene im Kulturbild südamerikanischer Indianer (in German). A. Schröder. p. 272.

- ^ Zerries, citing Wagley-Calvão (1949), p.102.[16]

- ^ Zerries, citing Roth (1915), p.173.[16]

- ^ Zerries, citing Gusinde (1931), pp.997–998.[16]

- ^ Zerries, citing Ehrenreich (1891 ), pp.67–68.[16]

Bibliography

[edit]- Blache, Martha (1977). Structural Analysis of Guarani: Memorates and Anecdotes. Vol. 1–2. Indiana University.

- Cadogan, León (December 1961). "Curuzú Yeguá (Apostilla a la interpretación psicoanalítica del Culto a la Cruz en el f olklore paragua)". Revista de antropologia (in Spanish). 9 (1–2): 39–50. doi:10.11606/2179-0892.ra.1961.110412. (Downloadable at ResearchGate)

- Fariña Nuñez, Eloy (1926b). Los mitos guaraníes. Brill.

[]] (1926) the Curupí lassos or binds (enlazar) women with his elongated penis, and the women are able to make a getaway by cutting it off.[2]

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

magalhães_b.1928was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Fariña Nuñez () "". Revista do Instituto historico e geographico brasileiro. Tomo special: Congresso internacional de historia da America (1922), 2: 311–331", quoted by Basílio de Magalhães (1928)[1] reprinted Fariña Nuñez (1926b), p. 215.